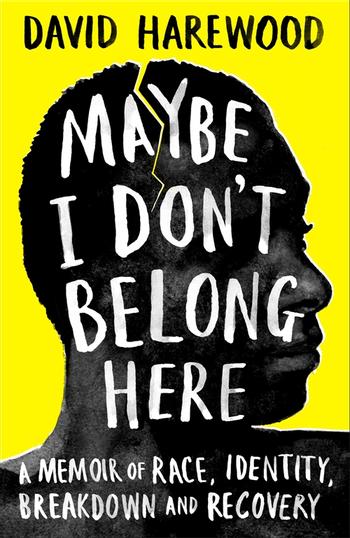

Raised in Birmingham in the 60s and 70s David Harewood’s life can read as the quintessential story of a working-class boy done good. Hardworking parents, a bar job after school until getting accepted into RADA, and from there a meteoric rise to Hollywood actor. It’s a story we’ve heard before and it’s true. But his memoir lays bare another story beneath the standard boy done good. Maybe I Don’t Belong Here navigates an upbringing marred by racial trauma, a young man struggling to belong, and how a man that once rubbed shoulders with Al Pacino, was sectioned in a mental institution. Twice.

Here are five things we learned:

- It Can Happen To Anyone

An important takeaway from Maybe I Don’t Belong Here is that it doesn’t matter who you are. Even if you are a successful Hollywood actor, you can suffer a mental health crisis. A standout moment in the book is when Harewood wakes up in a mental institution and thinks to himself,

‘I was sure I was an actor before this…I studied at a really good drama school and had lots of friends and laughed a lot. What the fuck happened?’

The reality is that whatever your position in life it can happen to you, and there’s no shame in that.

- There Is No Black In The Union Jack

Harewood explores the dissonance he felt growing up Black and British. As a child, he felt as British as chips. But there is a fundamental difference between feeling British as someone born and raised here and being treated as British by those around you. The phrase, ‘there is no black in the union jack’ was part of a song sung to David and other black children growing up in the 60s and 70s as they walked the streets of England. It was sung to remind them that their skin colour meant they could never truly belong here. Racism like this created a battle of identity that makes black people think maybe they don’t belong here.

- Racism Has A Mental Health Tax

Harewood’s memoir adds lived experience to the fact that racism takes a toll on the mental well-being of black people. He reveals black men are four times more likely to be sectioned than white men and black women six times more likely to be sectioned than white women in the UK. Aside from outright racism, existing in white spaces where you either feel invisible due to a lack of representation or due to being stereotyped, forces you to question who you are and negatively impacts your mental health. David’s psychosis reflected this trauma. He often imagined himself as a secret agent who could go where he pleased. Entering spaces without being questioned was a privilege he was rarely given in the real world as a black man living in Britain.

- It’s Important To Share

It is clear from the overwhelmingly positive reaction to Harewood’s earlier BBC Documentary Psychosis and Me that sharing real-life stories about mental health is important, especially in the black community. Someone like David speaking out about their own struggle is a catalyst for greater conversation on the topic and increased awareness. Stories like David’s are a spark of hope. Yes he went through this, yes it was difficult, yes this is something that disproportionately impacts us as black people, but he survived and so can we.

- To Be Black Is To Be British

As much as being Black and being British can feel like two identities that do not piece together reading Maybe I Don’t Belong reinforces our right to claim a British identity. Maybe a part of that identity is a shared experience of overcoming racism. David’s story of race and identity resonates not just with those that grew up in the 60s and 70s, but those born in the 80s, 90s, and beyond. Despite hardships, the black community has thrived in the UK. When David was a child black people were often banned from clubs and bars, so David’s parents and others hired halls and held their own parties. Carving a safe space to let their afros out and celebrate. They would not, could not, be stopped from celebrating their lives and their culture.

It’s hard to say what was most impactful about Maybe I Don’t Belong Here and narrowing it down to five was hard. Each chapter felt like a new experience but also gave the strongest sense of Déjà vu. This is not a bad thing. It felt familiar because his story isn’t just his own, it is a generational echo of a working-class kid from up north striving for more, of almost every black person of every age questioning their place in this country, and of anyone suffering through a mental health crisis. So, whoever you are it’s worth a read.

Maybe I Don’t Belong Here is published by Pan Macmillian and is available now

If you enjoyed this you may also like Five Books On Mental Health To Read