[It] is not to say violent protests are in themselves good; many protests have been condemned for allowing violent, wanton destruction to overshadow the issue at hand. But to diminish protest completely is to remove an integral part of people’s voice in society.

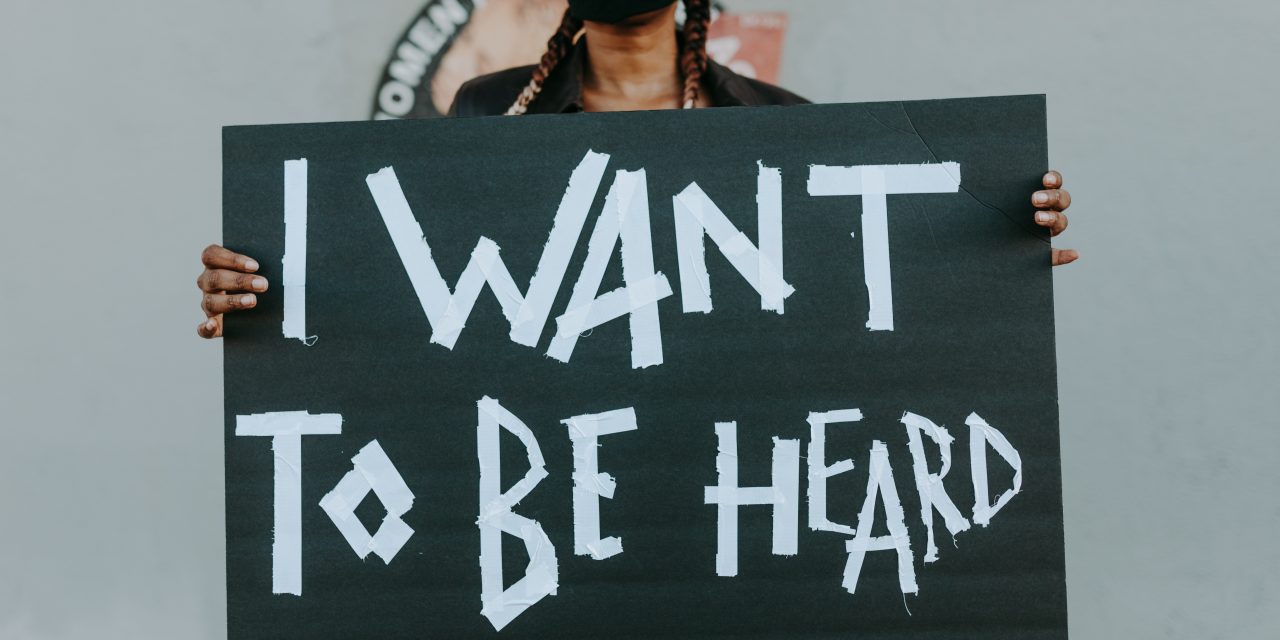

On Tuesday 16th March 2021 UK Parliament saw a bill pass it’s second reading, extending the power of the police and criminalising the act of protest. This reaction against public protest is not isolated to the UK. In a global context this is just one step amongst many, and serves to disempower the populace by removing their right to raise red flags on injustices they face. The context in which these changes come is harrowing, with governments twisting topical narratives to ostensibly validate their actions. In this we can see a growing trend to be found between people calling out for change, and governments trying harder not be to listen.

Rendering UK Protests impotent

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and courts bill (PCSC) includes a number of changes. Advocates of the bill highlight its harsher sentencing for serious violent crimes. Those opposing it, the bills removal of the right to protest. This comes in the shadow of the tragic case of Sarah Everard. Her murder by an active policeman sparked national discussions about women’s safety, and how we still accept everyday life being statistically more dangerous for those who identify as women. Touted by its supporters as a vital bolster to defences of women’s liberty, it aims to make women feel safer on our streets. What isn’t well highlighted by its supporters is that the vigil for Everard devolved into a show of force by the police and the silencing of the mourners. It was an opportunity for the government and local leaders to stand with their people and listen. Yet, a peaceful event turned into a banned protest, with heavy-handed policing and arrests that night. Women and mourners needed to come together in their pain, to decry the status quo, but found that their peaceful route was blocked.

The new bill would remove people’s right to stand for themselves, to question governance and stand against injustice, demonising peaceful acts of protest. In their reading of the bill, advocacy group The Good Law note “first, they significantly expand the police’s ability to place conditions on the right to public processions and assemblies and second they leave entirely open what those conditions can be”. The focus of the bill is to empower law enforcement, backing their judgement and the jurisdiction to dole out heavy penalties. It is because of this openness that this would risk any and all small, peaceful protests being banned, not the dangerous or violent instances. One person protests, noise levels or actions deemed a “serious annoyance” or “serious nuisance” would become a criminal offense with up to 10 years in jail. For comparison, the Crown Court has the highest penalty for grievous bodily harm (GBH) at 5 years. As noted in TGL’s explanation, the vagueness of these terms gives the police the power to judge and remove any protester under risk of this penalty, and only after can the person escape be means of having ‘a reasonable excuse’. Whether or not the person is able to provide this, the protest has been killed. We have to contend with the very real risk this vague language poses to the democratic right to protest. Non-violent protests would now be risking criminal charges to stand up for what they believe is right.

US protest – ‘tear gas, rubber bullets and batons…’

Days before the PSCS went through its second reading the US state of Kentucky passed an enforcement protection bill as well. Further empowering it’s officers in the wake of an ongoing tragedy. The bill states that any person who “insults” or “accosts” an officer “with offensive or derisive words[] gestures[]or other physical contact, that would [tend to]provoke a violent response from [] a reasonable or prudent person”, could see up to 90 days in jail and as much as a $250 fine. Clear of any knowledge of the recent displays of police brutality we’ve seen across the US, this law might have seemed like a sensible protection for police men and women. We do not, however, live in a vacuum. We live in a world where, in the last year alone, it has been made clear that a “violent response” by the police to protestors is a common occurrence. And like the UK’s bill the sheer vagueness of it means Police would be able to punish, remove or arrest people with near impunity.

In this moment in history, the burden of proof is heavy enough on civilians without taking further pressure off law enforcers who already act dangerously. The 2020 BLM protests did not just highlight the horrific, aggressive treatment faced by black or mixed race Americans (see here a list of just a few names and the latest outcomes of their cases). They showed indiscriminate and unfettered police brutality to anyone standing in their way. Police used weapons like tear gas, rubber bullets and batons in over half of the BLM demonstrations they engaged with. Even though these protests were seen as peaceful in over 90% of the cases. Journalists were beaten and chased, even whilst standing behind demarcated lines and identifying themselves as press. Where law enforcement turned up to protests armed for aggressive response, that a new law is needed to tell the people to be less aggressive is laughable. In the immediate wake of these atrocities, this not only speaks to the continued alignment with the police over the people but lawmaker’s utter disregard for the condemnation within and without its state lines.

Silence the opposition

These actions are not ones which defend the people, they are ones which silence debate. And the truly horrifying fact of these potential, probable new changes, is that they are proving what many fear; that lawmakers prioritise the appearance of social good without the substantive proof the people are actually reaping the benefits. It proves that the truth that two nations exceedingly proud of their democracy have clearly missed the fundamental tenant, ‘to rule by the people’. It is exceptionally harder to deliver on that if you cannot actually hear what the people have to say.

We cannot ignore the positive impacts protests have had throughout history. Women’s suffrage, race equality, class and wage rights, all have been shaped by acts of protest throughout time. These protests have not always been peaceful, and at times history has looked back on violent protest with a forgiving eye and agreed it was necessary for change. Acts of protest breed headlines, garner global coverage of difficult topics and can serve better where other methods of public outcry haven’t worked. That is not to say violent protests are in themselves good; many protests have been condemned for allowing violent, wanton destruction to overshadow the issue at hand. But to diminish protest completely is to remove an integral part of people’s voice in society. This UK bill isn’t about extreme and dangerous gatherings, it is about empowering officers to clear away any single or small group standing ‘annoyingly’, whilst the US bill empowers those already wielding the power. We are not addressing the problem of destructive malcontents using protests but the muzzling of victims who are already not being heard.

It’s amazing what a right leaning government can ‘hide’ during a pandemic. I really appreciate your views and highlighting this Orwellian move.

Glad you enjoyed reading. It’s such an important subject.